How to Fix the Performance Review-Once and For All

A few notable exceptions aside, the performance management process in most organizations is broken. It's time to end this.

The performance management process in most organizations continues to be as frictionless as a rug burn and as useful as the “scroll lock” button on your keyboard.

Despite hopeful pronouncements that regularly appear in the pages of Harvard Business Review and Fortune every couple of years, we're still stuck with a process that few are happy with. The body of evidence suggesting that traditional performance review processes are inefficient and of limited value is deep--and continues to grow.

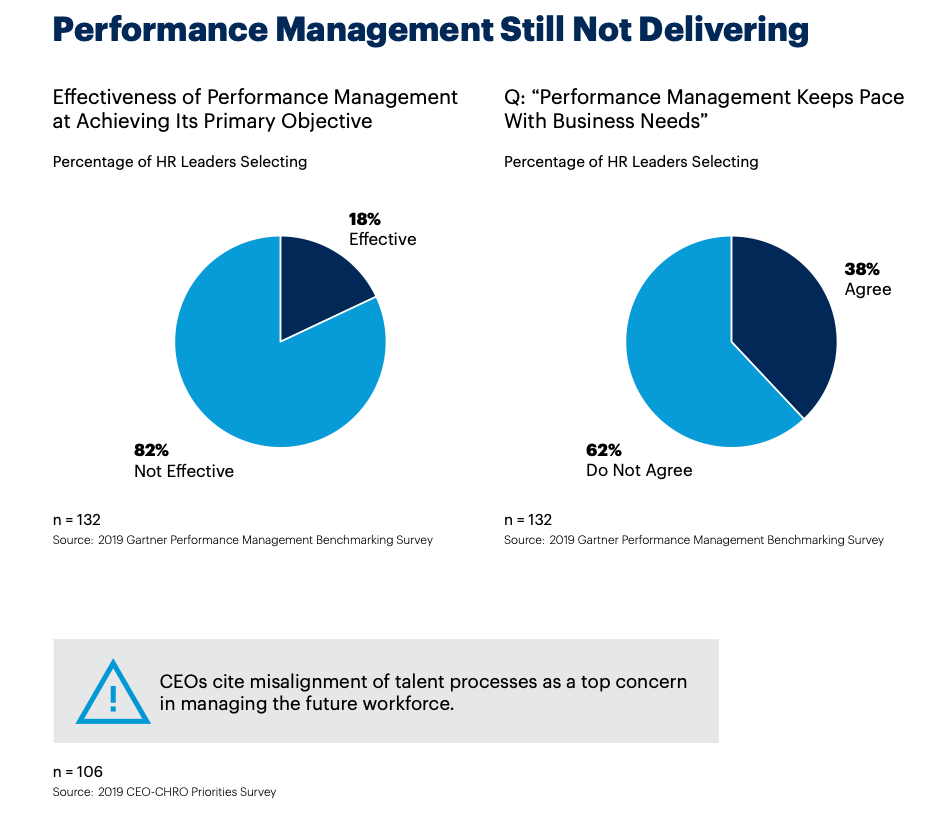

A recent report on performance management by Gartner, drawing on interviews with execs as well as a large-scale employee survey, is consistent with this trend. When even a vast majority of HR leaders--folks who probably aren't terribly keen to diss a process under their control--admit performance management is not achieving its goals or evolving fast enough, you know there’s a problem:

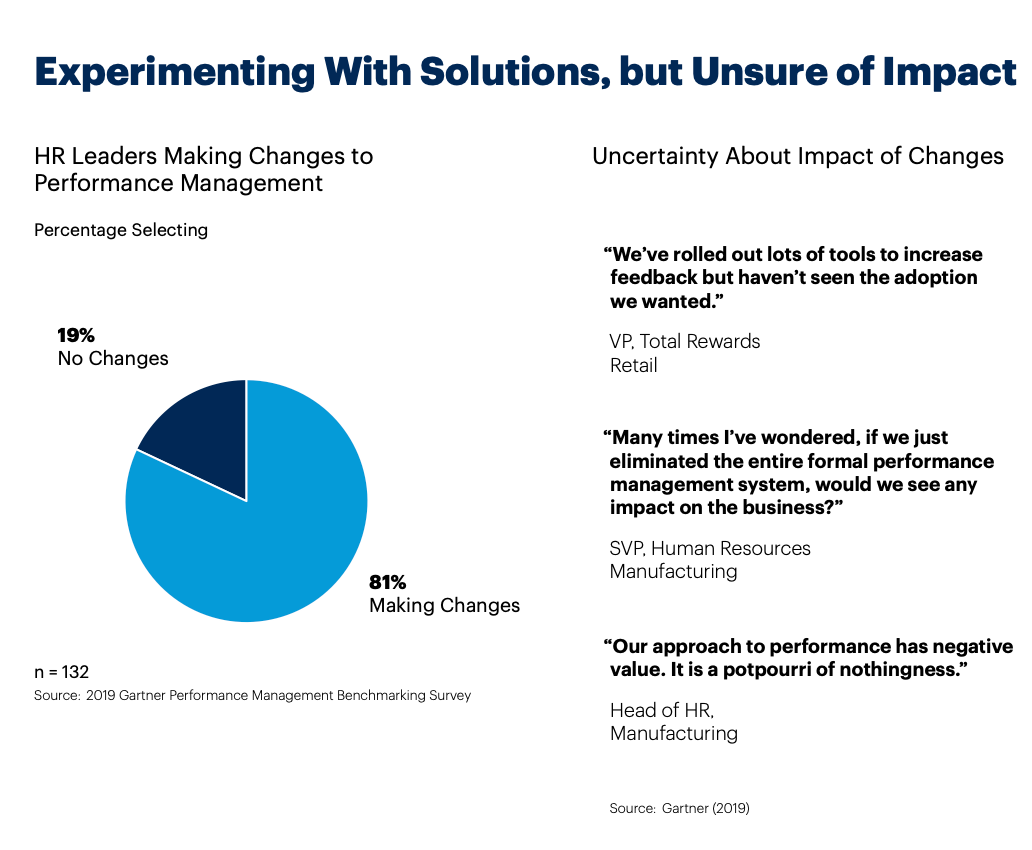

In fairness to HR, the lack of progress isn’t for lack of trying. A lot of organizations are experimenting with a variety of changes, like removing performance ratings, or moving from a yearly to a more frequent feedback cycle. Yet the impact of these reforms is uncertain at best:

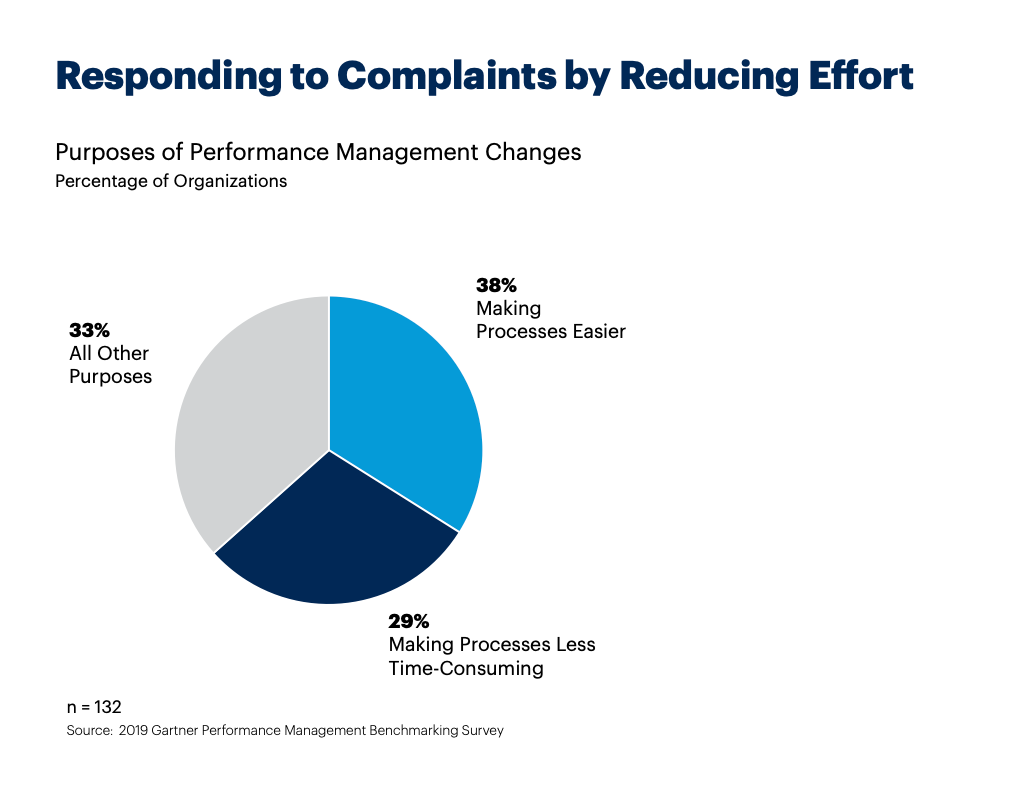

One clue for what might be behind the lack of progress is that the changes have been mostly focused on reducing friction:

Making the performance review easier and less time consuming can certainly help, but it doesn't solve the root cause of the dysfunction. The biggest problem with traditional performance management has to do with its excessive reliance on the judgment of one’s boss. Evaluating performance via the managerial chain of command introduces a variety of distorsions, both on the part of the rater (all kinds of biases and favoritism) and the person being rated and (needless fear and self-censorship). Despite the hype, boss-driven performance reviews remain the dominant fact of organizational life: 99% of the employees polled by Gartner indicated that their performance is evaluated by the direct superior, with only 17% claiming that teams played a role in evaluating employees.

In our book, Humanocracy, we highlight a number of approaches to managing performance that draw on more robust sources of input. The most obvious is peer feedback.

At WL Gore, a materials science powerhouse and management pioneer, peer feedback drives employee performance rating and compensation. Every Gore associate is given a list of 15-30 colleagues—individuals who work within or adjacent to their team. As an associate, your job is to force rank your colleagues by the value you believe they created over the previous 12 months. You rank only individuals for whom you have sufficient information. A typical associate will receive 10-15 ratings. Once the ratings are in, local contribution committees review the results and make subtle adjustments as needed. For example, if the average ranking for an associate puts her in the middle of a list of 25 individuals, but she was ranked substantially higher by top performers, her position might be nudged upwards. After the rankings have been finalized, associates are told in which quartile they were placed.

The committees then look at compensation data. Their goal is to ensure that an individual’s pay stays in synch with their peer-rated contribution. If the average pay rise in a given year is 4%, a modestly paid but highly ranked associate might get a 15% increase, while a poorly-ranked associate may get no raise at all. Gore’s peer-based compensation system pushes everyone to think about how they could add more value. You get ahead at Gore not by climbing a pyramid, but by growing your contribution.

Another powerful source of performance feedback is the customer. At Haier Appliances, all employees are part of small entrepreneurial units (called micro enterprises) and your compensation is tied to how well your unit does in serving internal and external customers. The microenterprises are small enough (7-10 people) that a combination of peer pressue and shared incentives create an efficient and self-regulating form of control. There's no need for six-dimensional competency grids, stacked ranking, and lots of paperwork--the marketplace provides a "review" of your and your team's performance, every day. Haier CEO Zhang Ruimin is only partially joking when he says that employees report to the customer, and not to a boss.

So, if you’re keen to fix the performance review process for good, consider introducing the following changes to how you assess people in your organization:

- Ensure that competence and performance ratings are peer-based, with at least five assessors for every individual. Make this data public.

- Give significant weight to peer assessments in all hiring and promotion decisions.

- Tie compensation closely to peer-based rankings.

- Redesign decision processes to give a great share of voice to those with relevant, peer-attested competence. Downgrade the influence of positional power in decision-making.

- Create customer accountability deep in the organization—for instance by tying the performance of back-office units to the success of the marker-facing units they support.